Even though I understand the statistics behind LLMs, I still can’t help but be taken in by the magic of their answers. At first glance, you ask a question, you get a solution — instantly, no need to slog through lines of code or endless documentation.

I knew that one of the strongest features of these new models was their ability to summarize text. To classify games on Gameaton, I wanted to leverage this strength to process massive quantities of data: thousands of games with hundreds of reviews for each one of them. By using motivational criteria and asking the AI to assign a score for each, I could build a database that would make it easy to compare titles — which games appeal to competitive players, which speak more to creative minds, strategists, and so on.

Of course, I was aware of the many potential biases that come with using an LLM for a classification task (hallucinations being the most obvious). So how could I ensure consistent scoring across more than 8 000 games? Through statistics, of course! With such a large dataset, the dispersion should be wide enough for every score to be represented.

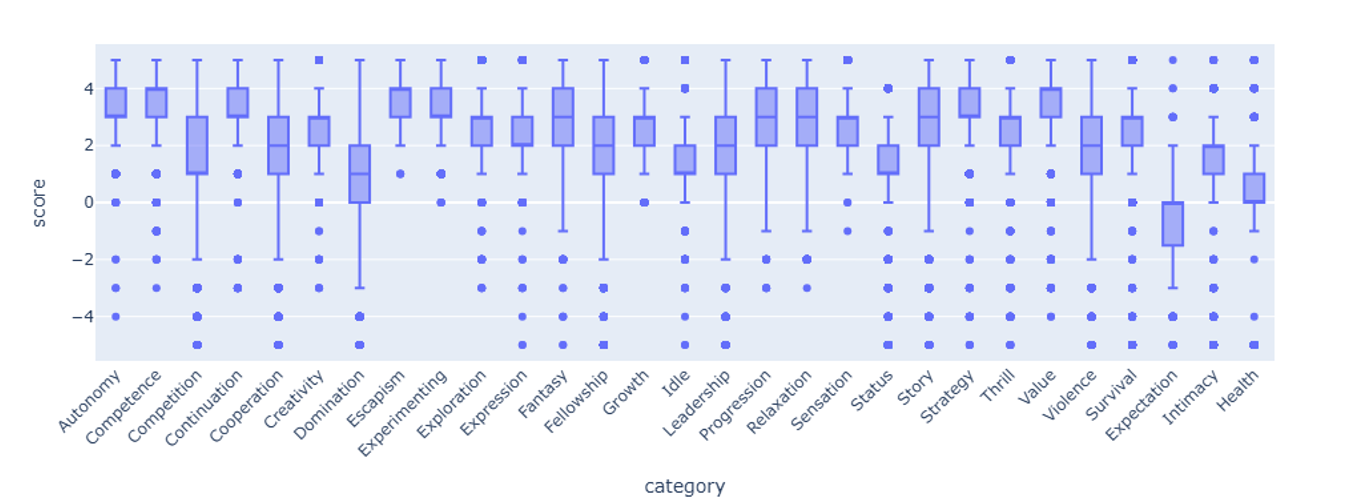

The result was clear: the scores were mostly clustered on the positive side of my motivational dimensions, even though I expected a much more balanced distribution. Something was off.

The Suspect: The Prompt

Without going too deep into the details, the prompt used for classification simply included a short explanation of each motivational dimension, then asked the model to rate each one from -5 to +5 depending on how well it matched the description. A score of 0 was reserved for games where the model didn’t have enough information in the reviews provided to decide.

I began to suspect that the way the prompt was phrased encouraged “positive” ratings, even though the scale could easily be inverted without changing its meaning. Let me explain: a highly cooperative game would receive a +5 because the “Cooperation” dimension was described as “Working with others toward a goal (e.g. teamwork, shared objectives)”. A non-cooperative game, in turn, would be rated -5. But if we flip the scale, the cooperative game would get -5 and the non-cooperative one +5. The positive or negative valence shouldn’t matter here — what matters is the opposition between the two poles on a single continuum.

From my experience as a player, I know that cooperative games are not the norm, so a median around +2 seemed overestimated.

By only explicitly defining the positive side of each dimension, could it be that the prompt itself was introducing a bias? As if understanding the opposite of “positive cooperation” — something like “Engaging independently (e.g. individual tasks, focusing on personal objectives, limited collaboration)” — required an extra step that the model was reluctant to take.

Another possible explanation lies in the ordinal nature of the scale. Since the ratings are not perceived linearly (there’s no strict rule for what a “3” means), the LLM could be biased by its own semantic perceptions. That’s already true for humans — and even more so for a model that “reasons” purely in linguistic terms.

Methodology

To test my hypotheses, I randomly selected a sample of fifty games and submitted them to four different prompts:

- All_values_defined.txt: a prompt where each score had its own explicit definition. Two immediate concerns: it’s very time-consuming, and by defining each grade I risked drifting away from the original social science framework that inspired me (I’m not a social scientist).

- All_values_defined_with_examples.txt: same as above, but with three game examples illustrating each rating. Same drawback, but examples are part of good prompting practices (that’s the E in the RISEN framework).

- Both_ends_defined.txt: a “lazy” version where I only define the meanings of -5 and +5, without specifying the intermediate values. I also take care to avoid negations, following Google’s prompting guidelines.

- One_sided_scale.txt: the original prompt I’d been using so far, where only the positive end of the scale was defined — my baseline for comparison.

Given how much manual work was required to define examples and explanations for each note, I limited the experiment to the first four motivations: Autonomy, Competence, Competition, and Continuation.

Results

Global Analysis

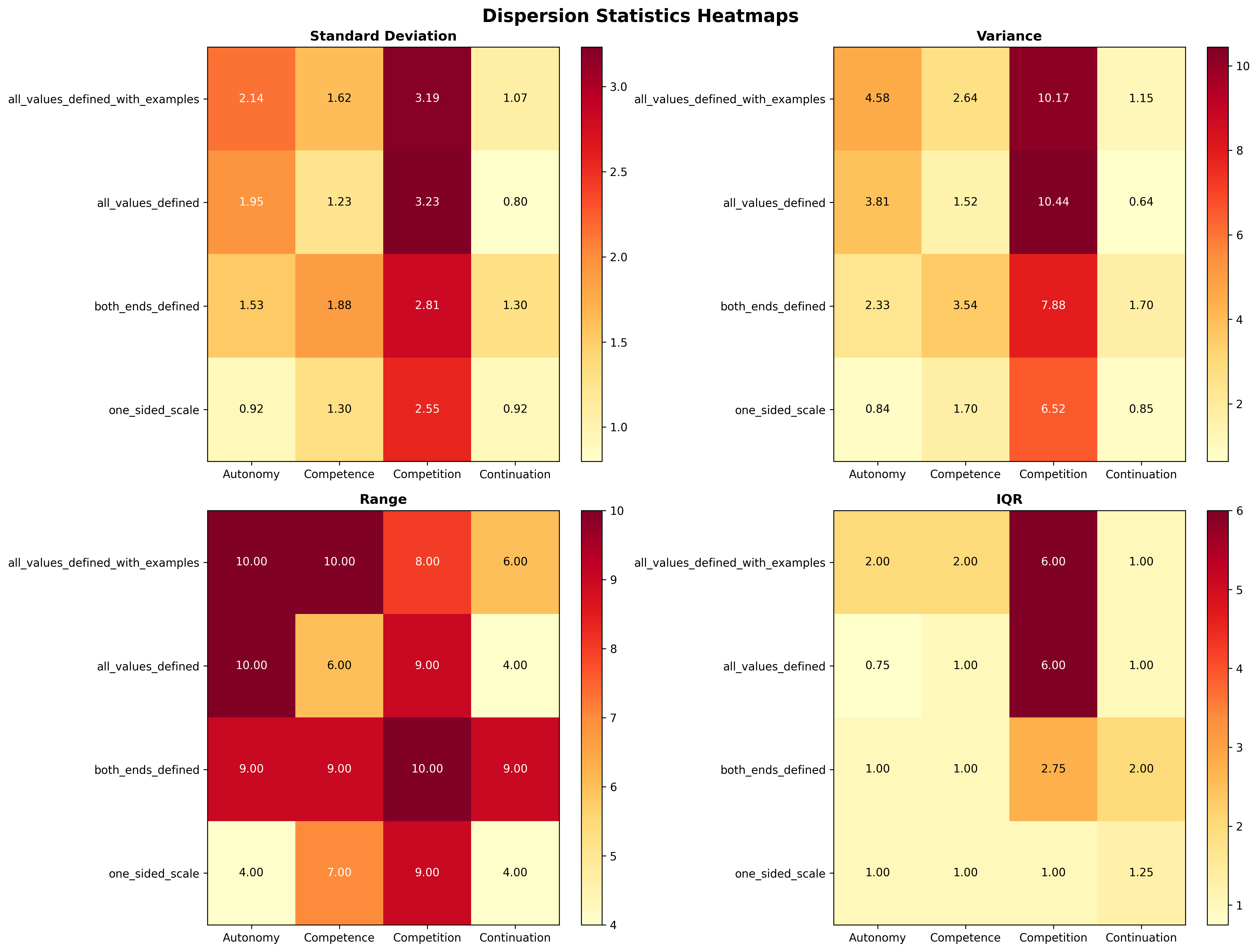

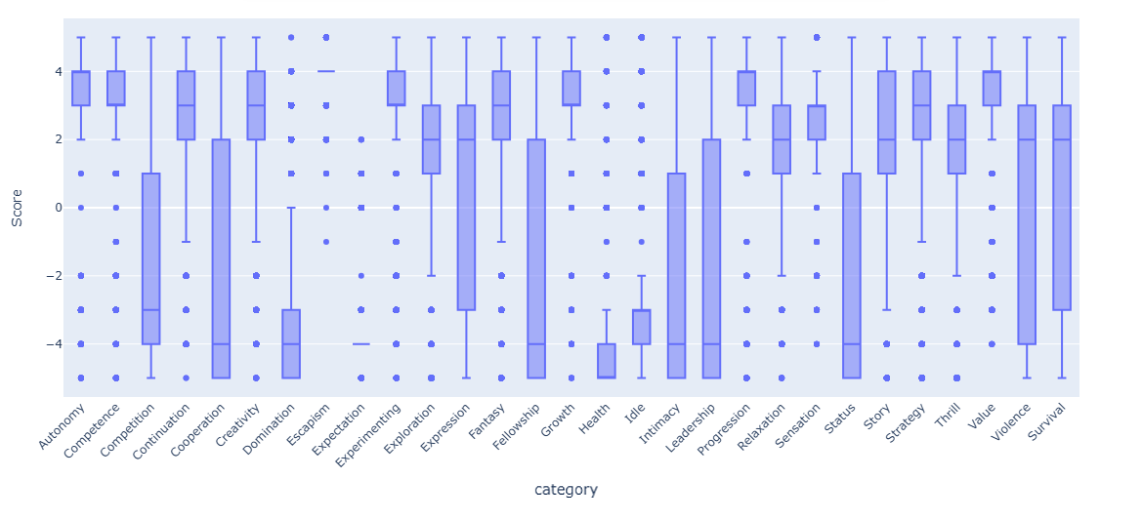

The boxplots didn’t point to a clear “winner,” though my first hypothesis — that the one-sided prompt produced a positive bias — seems confirmed. The other three prompts leaned more toward the negative end of the scale. The All_values_defined_with_examples.txt prompt also seemed to spread the scores out more evenly, though not consistently (median and Q1 were identical for Competition).

I decided to take a closer look at the dispersion of the data.

The three new prompts overall produced better dispersion, confirming that the way a prompt is phrased has a real impact on scoring. The Both_ends_defined.txt prompt was particularly stable, and the Competition dimension displayed the most uniform spread. Interestingly, the category itself influenced dispersion more than the prompt type.

The original One_sided_scale.txt prompt consistently showed the least dispersion, strengthening my decision to move away from it.

Individual Analysis

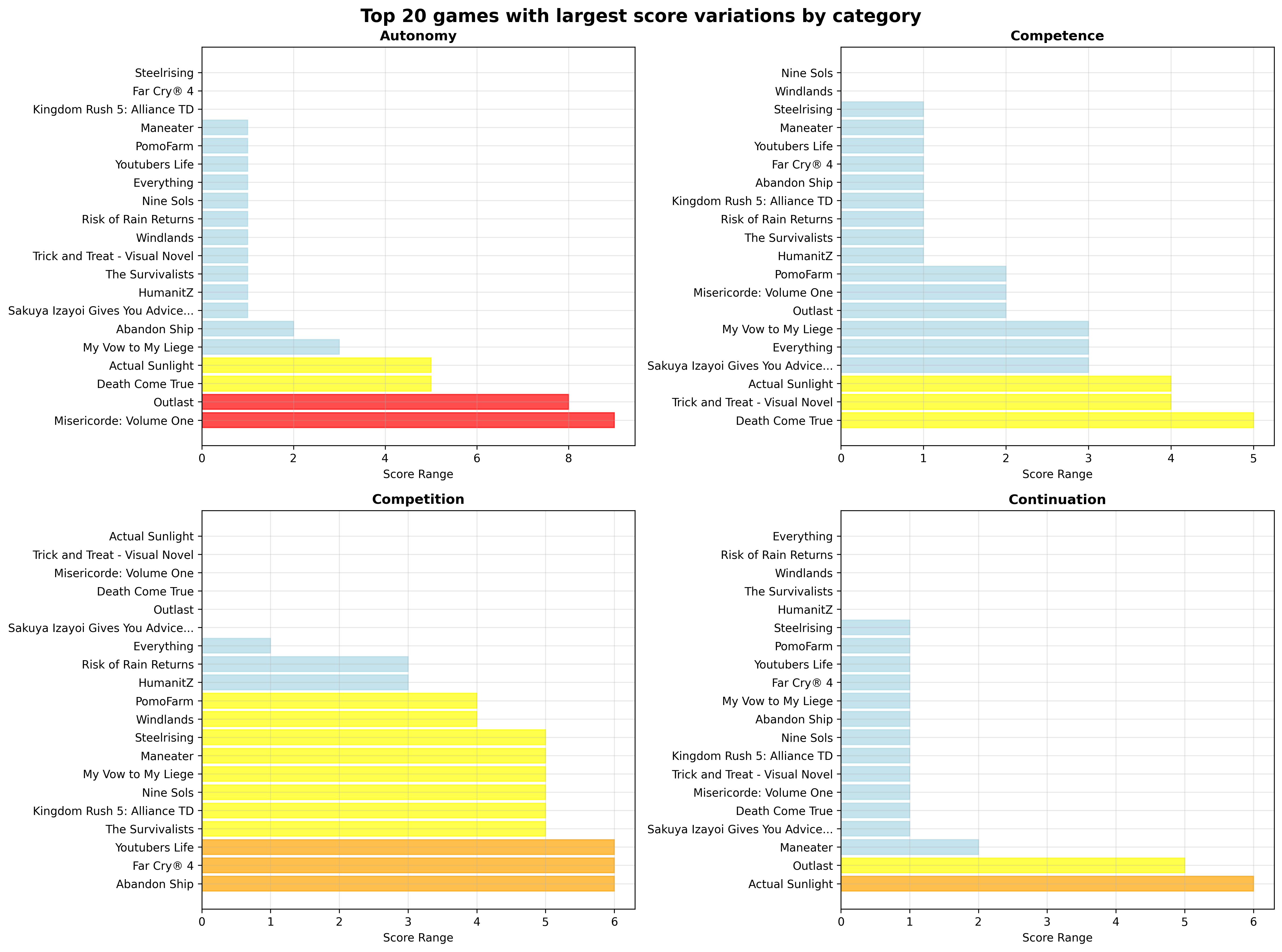

I selected games with the largest score differences across prompts to check whether certain formulations might induce rating bias. After all, it’s easy to artificially inflate variance through the anchoring effects from examples.

Most of the variation came from the Competition dimension. The All_values_defined_with_examples.txt prompt tended to be stricter than the others.

For example, with Far Cry 4, it rated competition at -5, arguing there was none, even though there is a competitive mode (arena). Similarly, Youtubers Life got a -5 despite featuring leaderboards. The prompt wasn’t flawless on other dimensions either: for Outlast, autonomy was rated -4, which felt harsh for a game that still offers a decent range of actions (camera, movement) even within linear levels. The other prompts produced more balanced results.

The All_values_defined.txt prompt, surprisingly, was far too lenient. In the Far Cry 4 example, it shifted competition to +1 just because of the arena mode. On other games, like Steelrising, it tended to equate lack of competition with a neutral 0:

“Competition unrelated; no evidence of multiplayer or leaderboard features in reviews or general knowledge.”

Meanwhile, Both_ends_defined.txt made fewer mistakes, but more striking ones. For Misericorde Volume One, a kinetic visual novel, it rated Autonomy at +4, arguing:

“The game is a kinetic novel with no player choices, but players have freedom in how they engage with the story and interpret characters, reflecting a strong sense of personal agency in narrative experience.” (!!)

So, no perfect prompt. None performed flawlessly, but all improved data dispersion, which led me to ultimately choose Both_ends_defined.txt.

Several reasons tipped the scale:

- Significant time savings: defining two extremes instead of ten values doesn’t scale linearly: writing nuanced definitions for each score takes far longer than writing just two.

- Scientific humility: since I’m not a social science researcher, defining each score risked distorting the original measurement framework.

- Error management: a single large mistake is easier to spot and correct than many small, hard-to-detect ones.

Gameaton is an iterative project. Maybe one day, there’ll be human review integrated or a deeper analysis focused on outliers (e.g., games that deviate strongly from genre, platform, year, or overall ratings).

After applying the new prompt to the full dataset, the result was satisfying: the positive-side bias was gone.

Conclusion

In my daily use of LLMs, I value instantaneity: writing as little as possible to get as much as possible. The growing contextual understanding in systems like OpenAI’s chat models encourages this habit of quick prompting. And most of the time, it works: the answers are surprisingly good, and with experience, you start intuitively guessing what the model might misunderstand.

Given that, it’s tempting to think that prompt engineering is just a passing trend — soon to be made obsolete by smarter, more self-correcting models. Whether through larger training datasets, better reasoning capabilities, prompt ambiguity detection, or external tools, there are still many paths unexplored to reduce user burden.

Yet for zero-shot classification tasks, where scale and cost-efficiency matter, I’ve found that this much-maligned “buzzword” discipline actually hides real practical value.